I was excited about Behind These Doors the moment I heard about it.. Queer historical romance with open polyamory? Yes please. It’s gorgeously written, and offers such a nuanced story about queerness and class and misogyny. I loved watching the romance between Aubrey and Lucien unfold, and the polyamory representation was deeply compelling and felt very real. I am excited to share this interview with Jude about one of my favorite historical romances I’ve read this year.

A Bit About Jude

Jude is a bi, demisexual, pagan woman of colour, is a carer, and has been chronically ill for most of her life. Born in temperate England, she grew up in tropical Zimbabwe, and has now settled permanently in the sub-arctic Shetland Islands in Scotland. Growing up in a country where it was understood that Muslim men might have up to three wives, she’s always considered it perfectly reasonable for people of any gender to have multiple partners, provided everyone involved is happy with that. She lives, comfortably polyamorously, with her life-partner of 27 years, and their three kids.

For several years, she was a 1st Century Roman and Early Medieval re-enactor. Her primary focus was combat and target archery, and her secondary, living history and craft demonstrations. She has hung up her bow and cedarwood arrows, and now makes silver and bronze jewellery instead.

An Interview with Jude

How would you describe yourself to a new reader just discovering your work?

My tagline is: “Jude Lucens writes about marginalised people affiliating and building family in the face of restrictive, often punitive, social norms”, which pretty much covers it in brief.

The characters I write tend to be basically decent people who are marginalised in one or more ways, trying to make their way and live their truths in a world which doesn’t make that easy. Along the way, they encounter people with marginalisations and psychological wounds different from their own. They try to do the right thing, but they’ve absorbed some of the prejudices of their world. Even as they battle the monolithic social prejudices arrayed against themselves, they don’t always immediately recognise other characters’ struggles, or their own relative privileges.

Although they work on raising their awareness throughout the story, these issues are seldom completely resolved by the end. A few conversations and encounters can’t magically give someone a comprehensive and visceral understanding of their privilege, or of another person’s experience of oppression. This doesn’t make for light reading, but I need to write stories that feel true to me.

What sparked Behind These Doors for you? What made you want to write this particular story

Behind These Doors started accidentally. A Facebook group I belong to ran a ‘Caption the Leyendecker’ game, and the picture was so evocative that I wrote a short paragraph rather than a caption. People liked it, so I wrote a second paragraph, then a third. And then a few people said they wanted to read the whole story, which startled me. Anyway, I wrote the short story for those who’d wanted it. Rather mawkishly entitled The Taste of Your Tears, it was a clumsier version of what is now Chapter 1 of Behind These Doors.

That was supposed to be the end of it, but creative obsession is a terrible thing. Having agreed to entertain the characters long enough to write a short story, I discovered they were inconsiderate guests who wouldn’t leave at the proper time. Lucien and Aubrey wanted more than a single, rather angsty, night and an ambiguous promise; Henrietta and Rupert demanded proper acknowledgement of their role in Aubrey’s life; Edgar indignantly insisted he wouldn’t have been defeated so easily. I said I absolutely wasn’t going to write this seriously, because I didn’t have the bandwidth to research another period when I’d just spent years researching 1st century Roman Britain for a (to date, unpublished) fantasy novel. As it turned out, between endless nudges from imaginary people, and generous enthusiasm from a few real people, I did.

I really appreciated how your queer characters had other queer folks in their lives in Behind These Doors. I treasure stories where queer MCs aren’t alone in an allocishet book world. What are some of your favorite books with queer MCs who are connected to other queers

’Nathan Burgoine’s Of Echoes Born is a book of short stories about queer men. As you’d expect in an anthology, especially one which covers a range from contemp to fantasy, some stories spoke to me more than others, but they were all beautifully written and full of heart, and the stand-out ones were absolutely transporting.

Kris Ripper’s Kith and Kin is a glorious and diverse contemp saga about family—both blood and found. It addresses a multitude of issues such as deep-seated family conflicts, recovering from being in a cult, and adoption, all with compassion and humour, and in terrific prose.

Alexis Hall’s Kate Kane: Paranormal Investigator series is a fabulous semi-parodic pastiche of every urban fantasy/paranormal trope, but with its own highly creative, hilarious, and gory spirit.

KJ Charles’ Society of Gentlemen series probably needs no introduction. In Regency England, a group of queer aristocrats band together for mutual protection from a cisheteronormative culture. Funny, touching, strong on class awareness, and brilliantly written, it features diverse supporting characters.

Liz Jacobs’ Abroad is a beautifully written duology about an American Jewish-Russian student who arrives for a year of study in England, and finds the support he needs to live his truth in a close-knit, diverse group of queer friends.

I love that Behind These Doors is a polyamorous queer historical romance that shows a complex polycule; it’s the first one I’ve ever read. Tell me about preparing to tell a story like this. What kind of research did you do? What did you draw from when writing about polyamorous queer folks in Edwardian London?

Wow! I’m surprised they’re so rare. I hadn’t seen any myself, but assumed they were out there and I just hadn’t looked hard enough.

Several books on the general history of British queer people—some specifically on Londoners—informed the historical aspects of the novel. So, for instance, Hyde Park and St James’ Park really were known cruising grounds, and Piccadilly Circus and Oxford Street were so well known for it that police there were extra vigilant for any slight gesture that might be interpreted as one man indicating sexual interest in another. On the other hand, Edward Carpenter, the gay activist/socialist philosopher/poet whose work is mentioned in Behind These Doors, was in a long-term, live-in relationship with George Merrill from 1898. He was emotionally destroyed by Merrill’s death in 1928, and died the following year. Despite the prejudices of the time, he was buried in the same grave as Merrill, and they share a headstone.

I also took into account a well-known, apparently polyamorous relationship from further back. In the late 18th century, Lady Elizabeth Foster lived with the Duke and Duchess of Devonshire as the duke’s acknowledged lover, and it seems possible the duchess was also her lover. Having a mistress was perfectly expected of a man of the period; having your mistress live in your family home—especially when your wife lived there—was scandalous. Equally scandalously, Lady Elizabeth’s children by the duke were raised by the duchess, together with her own legitimate children.

It’s impossible to know whether this is what we’d think of as a polyamorous relationship today—there were rumours of misery, and all three of them had other lovers from time to time, so some suggest the duchess was just putting a good face on things—but she was also said to consistently display an unreasonable attachment to Lady Elizabeth. And when the duchess died, Lady Elizabeth and the duke were both reported to be inconsolable. They married three years later. At Lady Elizabeth’s own death, almost 20 years after the duchess’, it was discovered that the locket she was wearing contained a strand of the duchess’ hair, and that the bracelet which lay on the table beside her deathbed also contained the duchess’ hair.

It wasn’t an equal relationship, the duke was highly autocratic, and communication between them all seems to have been terrible at times, but that looks a lot like an open-ish polyamorous triad to me, regardless of whether the women were sexually involved with one another.

I didn’t find any direct references to a polyamorous-appearing relationship within the period (which isn’t to say they didn’t exist, only that I didn’t find them). However, many of the legal, social and cultural issues which cause stress in modern polyamorous relationships also existed then, and many of those same issues—limitations on marriage, couple privilege, cis male privilege, wealth privilege—appear to have strained the Devonshires’ relationships. Then as now, even if everyone genuinely loves one another equally, so much conspires to privilege one person or dyad above another, and to mark one dyad out as primary, even if that’s not what any of the people involved really want. So I inferred that these problems were more or less universal in polyamorous relationships, at least in British culture. I imported them and adapted them to suit the characters and the specific background of the period.

It was also important to me to show that some people actively want a secondary relationship, and that it doesn’t mean there’s any less love there, or that the relationship is any less valued by the people involved, or by their other partners. Obviously it’s awful to be forced into a secondary position when that isn’t what you want, and far too many people have been badly hurt by that. But, in my experience, it can also be something some people actively want. They may not have the time or energy for a primary relationship—which could be a temporary or permanent state of affairs—or they may feel more of a strong, friendly, committed love than a passionate romantic love, and not need to see their lover all day every day. I don’t think that choice should be denigrated as lesser, or less committed, just because it doesn’t fit in with a particular cultural ideal of love. It also seems unlikely, when it’s a strong preference some people have today, that it wouldn’t have existed at all in the past, so I included it.

I really appreciated the different ways Behind These Doors engaged with and challenged misogyny, from the way Miss Enfield is treated at work to the complexities of the suffrage movement, from the ways Henrietta is treated by her brother to the ways sexism was central to one of the core conflicts in the story. It is rare for romances with queer men MCs to engage with misogyny in this way; can you tell me what motivated you to make this a central part of this particular story?

I originally set the story in 1908 (under the impression that was the date of the painting the story was based on) but once I’d acknowledged I was actually going to write an entire novel, I started looking for interesting background events, and found a lot happening around the women’s suffrage movement in 1906. As a long, passionate, and eventful struggle, it seemed a perfect anchor for a novel (and, later, for a series) so I moved the manuscript’s date to match it.

Having decided on that anchor, it was obvious that women’s rights, and misogyny in general, must be one of the themes. Ex-mill worker Annie Kenney gave a speech at a Women’s Suffrage meeting in 1906 about the abuse of working class women by men at work and at home, so I made that a background concern in the book, too. A lot of working class women were involved in the fight for women’s votes, and Sylvia Pankhurst—an important WSPU organiser in 1906—was a communist who materially supported working class women in the East End of London. So women’s rights broadly, rather than just votes for women, became part of the story.

The overarching thread of the battle for women’s rights is important in itself, and is the backbone of the series, but it also became a macrocosm of the various oppressions experienced by the characters in the book. I wanted to show how misogyny affects women at all levels of society, even those you’d think would be safest from it. I also wanted to show how it’s used as a stick to beat men who deviate even slightly from masculine gender norms (the fact that “Molly” was a common term for a gay, bi, or gender non-conforming man from the 17th century onwards tells us that pretty explicitly) and how, once again, class doesn’t completely protect anyone.

Most of all, I was trying to write something that felt real. Characters who could really have existed; events which could credibly have happened. Misogyny naturally came along with that, because it was a world even more deeply steeped in misogyny than ours is now (in the UK, at least: I can’t speak for any other country).

You write such complex and compelling characters, and not just the MCs but the secondary and minor characters feel deeply drawn and nuanced. How do you build this kind of complex characterization?

Thank you so much!

I firmly believe that everything we write carries a political message, so I don’t want to write any character as a de-humanised place-holder. A lot of this story is set in aristocratic spaces, where it’s easy to portray working class and poor people as convenient, ever-obliging automatons, but that’s offensive and unrealistic.

I grew up in a culture where it was common for people of all races to employ poor black people to do their housework and gardening and care for their children. It was very clear to me that, while some people did become genuinely attached to the families they worked for (and vice versa) they were never mindlessly loyal, and the power imbalance was too great for them ever to completely trust that relationship. Many didn’t like their work or their employers, but had to smile and seem agreeable anyway, sometimes in the face of condescending praise or unreasonable expectations, sometimes while being disparaged and insulted to their faces; often in the face of racism and being talked down to, even by children. And besides those work difficulties, they had their own lives and families and other struggles, though an oblivious employer wouldn’t necessarily see that.

It matters to me that every character is a whole person: that I know their background, what they care about, and what their struggles are; that every one of them has a life of their own running alongside the action of the story, even if it doesn’t appear on the page. Once I know the characters really well, it’s easier to portray them having nuanced responses to the events around them—responses which (I hope!) can be picked up by the reader, if not by the viewpoint character.

My starting point was the painting that inspired the story, drawing personality and attitudes from expressions, clothes, and accessories. As I got further into the story, I completed character questionnaires for everyone in the polycule, but when I look back at them, they’re not very accurate (though they gave me some confidence in the beginning, which is also valuable). My partner helped a lot: periodically dropping everything to brainstorm characters and plot with me, and even doing some background research. But most of the character building developed organically as I wrote: from each character’s history, class, and personal world. I wish I could work all that out in advance, via character sheets, because I’m sure it’d make writing a lot quicker.

Sometimes, once I have a reasonably clear concept of each character, I write a character reaction, then think, “Wait. Why did they respond that way? Where does it come from?” So sometimes backstory and motivation evolves from the narrative, and is later woven back into the rest of the story during rewrites.

Point of view makes a difference, too. Lucien is working class but mostly grew up on the edges of the aristocracy, so he’s painfully aware of how aristocrats view working class people. He’s also terrified that some of their attitudes may have rubbed off on him. As a result, he makes a point of paying attention to the working class people around him rather than letting them vanish into the background of his awareness; of considering their interests, and of bearing in mind the issues that might affect each person. Of consciously giving them equal—or greater—space in his mind than aristocrats. So when we’re in Lucien’s point of view, we see working class people in a heightened, almost spot-lighted, way compared with when we’re in Aubrey’s point of view, because Aubrey doesn’t much notice or think about working class people unless they’re doing something that directly affects him. That contributes to consolidating Lucien’s character, but also to bringing to life the working class characters around him.

Another consideration is fine detail and precision. How does this character speak? What words do they use? How do they move, and why? Aubrey’s valet moves like a ghost because he’s been trained to be as unobtrusive as possible for better service, while Hettie glides because she’s learned that apparent conformity to a particular gender ideal will help her achieve her goals better than outright rebellion (for now!). Edgar stomps because he’s learned that, as a man of his class, he can get his way by throwing his weight around, while Mrs Emmott, Lucien’s landlady, bangs and slams because she’s permanently overtired, angry, and fearful, and is trying to intimidate her lodgers pre-emptively, in self-defence. Without context, Mrs Emmott could be read as crass and uncultured—a clumsy working class foil for Hettie’s aristocratic grace. It’s really important to me not to reinforce that kind of prejudice, so I delve deeper into character motivation in the text, even if it’s just a line or two.

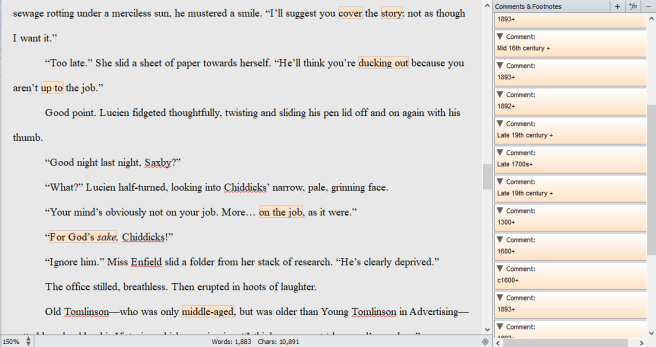

The language a character uses—whether in dialogue or in viewpoint narrative—helps locate the reader in the historical period and also provides clues to class and character. Green’s Dictionary of Slang was an invaluable reference, as well as Dictionary.com, which provides the etymology and first recorded usage for a lot of words (though not all, sadly). Things written in the period—even throw-away snippets—help; for instance, a comment complaining that the working classes use “bloody” in every other phrase. That doesn’t acknowledge upper class use of the same word (and they did use it) but does frame it, usefully, as a word which was disapproved in high society but more freely accepted among working class people—who, let’s face it, probably had a lot more to swear about! No doubt I missed a few, but I spent an enormous amount of time checking and double checking the slang in Behind These Doors, as well as any other words that looked remotely as though they might be modern, to make sure they were in use in 1906.

Because the characters developed over the course of the book, I needed to rewrite earlier chapters to ensure consistency throughout. But by the time I’d finished the novel, I was so accustomed to words I’d read over and over again that I couldn’t clearly see all the errors. Fortunately, May Peterson noticed several discrepancies, including in Aubrey’s character, where his personality early in the story didn’t seem to match his character later on, and set me on the right track. So, among all their other skills, having a good editor is essential to building strong characters, at least for me.

You drew an intricate web of characters in your polycule who are navigating multiple relationships with varying degrees of risk and power in these relationships. This isn’t your average romance where you can use a beat sheet to structure it or use other romances as models. How did you figure out how to structure this book? Tell me about the craft of that, of plotting these complex sometimes fraught connections, of deciding who to include in which scene and how you kept track of all these moving parts?

It was a struggle, and I often thought I was simply not clever enough to write this book the way I envisaged it, but I couldn’t see how to simplify it without making it shallow and less ‘true’. I got absolutely stuck several times, and each time I tried to outline the rest of it using beat sheets. Each time, the first couple of scenes were fine but from there it degenerated into something so cliched it made me wince. On the other hand, at least I had a couple of scenes I could write.

More than half-way through the novel, I discovered Dara Marks’ Inside Story, a screen-writing book which advocates a theme-based approach to plotting. The basic concept resonated with me, but it didn’t really help with plotting, even when I made up beatsheets based on her work (that’s a personal thing: other people do find this system helpful for plotting). On the other hand, the premise helped me keep the novel on track thematically, which was really helpful as I was trying to manage several large themes.

I use Scrivener software, which made it easy to keep track of notes and research, as well as allowing for quick flipping between scenes to cross-check facts, verbal tics etc. But essentially, Behind These Doors was mostly pantsed, was revised and adjusted multiple times as I was writing it, and was then fully revised so that it all hung together. The only way I could seem to get ahead was by putting myself into the mind of whichever viewpoint character I was writing, and simultaneously into the minds of the characters he was interacting with, while bearing in mind the world they were living in. The power differentials and the ways characters approached them came completely from their individual backgrounds and temperaments, their positions in the world, and their status relative to the other/s.

In terms of who to include in which scene, I’d decided early on that this novel would have only two points of view, however tempting it was to broaden it. And because I was using close third person point of view, the characters could only know what they experienced or were told, which was limiting but also helped keep the story tighter.

The actual historical events of the period were set in stone—I didn’t want to mess with them by shifting the date—so things had to happen around those anchors. That was both an advantage—in keeping me closely on track—and a disadvantage, as I had to shuffle the dates of fictional events around to make them fit the historical ones, while ensuring that they fit in with Lucien and Aubrey’s set nights together, and also that fictional events didn’t move so quickly or so slowly as to be inconsistent with the characters’ personalities.

In terms of keeping track of the moving parts of character relationships and interactions, it was all in my head. It was a bit of a headache at times, but since the interactions unfolded from each character’s history and personality, they were very consistent, and that consistency made things easier to remember. By the end, the characters were more or less writing the story themselves, but it was a struggle to get to that point.

Professional development editing made a big difference, too. Among other valuable feedback, KJ Charles identified a thread which wasn’t pulling its weight as part of the main story, and which she said needed either to be cut altogether or to find a relevant job that served the main narrative. I was pulling my hair out over that for days, but once I saw the way forward, it pulled several elements together and improved the whole story terrifically. I’ll never publish a book which hasn’t been vetted by a good development editor: I get too close to the story and can’t see the wood for the trees.

Overall, plotting and structuring Behind These Doors was a frustratingly slow process, and I’m sure there must be a better way. I’m currently trying to improve my plotting and outlining, because I think I’d get stuck less often and it’d speed things up. (I’m a horribly slow writer).

All of the relationships in your polycule are impacted by class, class expectations, and class differences, though Lucien and Aubrey’s is the starkest in this regard. I love this element of the story and the way that you engage with it in that relationship in particular. Can you talk a bit about writing this aspect of the story?

From the beginning, I was determined that this story would tackle issues of class. We’re all familiar with the moral outrage that was (still is!) poured upon queer men, but what’s less well-known is that they were regarded as peculiarly prone to undermining the strict social order. Edward Carpenter, who I’ve mentioned before, was an example of what they feared. An upper middle-class, highly educated man, he appears to have been exclusively attracted to working class men. His life partner, George Merrill, had been raised in a slum and had no formal education.

Carpenter himself, in 1908, noted this democratising tendency of queer people:

“It is noticeable how often Uranians of good position and breeding are drawn to rougher types, as of manual workers, and frequently very permanent alliances grow up in this way, which although not publicly acknowledged have a decided effect on social institutions, customs and political tendencies.”

This concern that queer men were undermining the social order was still being voiced in 1954, at the trial of Peter Wildeblood—a trial which eventually led to homosexuality being decriminalised in England.

An issue so inextricably linked with queer men in the political consciousness of the time absolutely had to be part of a historical novel about queer men set in that period. Simply loving a man of different class, and being loved back, was a deeply subversive act. I’m sure in a matriarchy with similar prejudices queer women would have been regarded as the agents of social change, but since it was men who had the most power to alter institutions and attitudes, it was queer men who were targeted.

In terms of the actual writing, my upbringing had a large influence.

I grew up in Zimbabwe before independence, in a segregated society where class was pretty much synonymous with race. And I don’t mean ‘segregated’ metaphorically: when I was growing up, all government schools were still racially segregated, and teachers generally had different levels of training depending on their race, which had a knock-on effect on their pupils. Some religious private schools weren’t segregated, but even the most highly educated black person would always be socially outranked by a white person, no matter how ignorant they might be.

In terms of privilege, mixed race and desi people ranked somewhere in the middle. But that ‘middle’ was a range, not an absolute. For the mixed race community, at least, skin shade made a big difference. A lighter-skinned person was more admired and would almost invariably get the job ahead of someone darker. Some—including one of my aunts and a couple of my cousins—pretended to be white to access privileges; they blanked their darker relatives in public, and excluded them from their homes.

Lucien is white, but he reflects some of the issues from that time and place of a relatively privileged, very light-skinned mixed-race person who could “pass” if he tried to, but who instead chooses peace of mind and his own people. Who has a strong attachment to less privileged people within his group, and yet never completely belongs because, however clearly he understands the issues, he doesn’t share their daily experiences of systemic oppression. Not that he’d want to suffer unduly, or that I’m trying to idealise lack of privilege—he’s incredibly fortunate—but it does distance him from his community.

I didn’t deliberately set out to write Lucien’s character with all this in mind, but since it’s very much part of my own and my family’s history, that’s what came out. There’s a wide range of skin shades in my immediate family, as well as in my extended family. As a result (apart from those who chose to ‘play white’) we’ve often had to insistently claim one another when strangers—both black and white—queried our relationship and outright disbelieved that we could possibly be related. I’ve heard “No, she can’t be your sister” way too many times.

That’s what Lucien is about. Holding tight to his family and his people, and consciously rejecting the temptation to assume a higher status, because it’d mean betraying people he loves and denying his own roots, which he values. He desperately wants Aubrey, but he doesn’t want to lose himself or his connection with his people along the way, and he’s wary of Aubrey’s oblivious prejudices and privileged expectations.

Is that a credible depiction of a white Edwardian man who’s been raised as Lucien had? The issues don’t match exactly, but I think the rigid racial divisions of my childhood, which were based on Victorian prejudices, can reasonably be partially mapped onto the rigid class divisions of Edwardian England, which were also inherited from the Victorians.

What’s next on the horizon for you?

I’m currently working on the next Radical Proposals book. The resolution in Behind These Doors left everybody in a relatively good place, but was also highly problematic for Hettie. I knew that even as I wrote it, but the book was already very long. Besides, I didn’t want to undermine the novel with a sub-plot that diverged from Lucien and Aubrey’s; or the character by compressing the resolution of her arc into a single chapter. In addition, telling her story through Aubrey’s eyes (since Hettie isn’t a viewpoint character in Behind These Doors) seemed an emotionally violent thing to do, particularly as the problems she faces are rooted in culturally-sanctioned male dominance. So Hettie’s getting her own book (f/m/m), working title: A Woman’s Place.

If all goes to plan, the third book will be Madeleine Enfield’s (f/f).

I’m also re-writing a historical fantasy novel I’ve been working on sporadically since 2004. It’s definitely not a romance. The MC is a neurodivergent wolf-shifter Roman patrician army officer in 1st century Britain, and the book has multiple content warnings as it covers issues including imperialism, colonialism, and brutal conquest.

More About Behind These Doors

Lucien Saxby is a journalist, writing for the society pages. The Honourable Aubrey Fanshawe, second son of an earl, is Society. They have nothing in common, until a casual encounter leads to a crisis.

Aubrey isn’t looking for love. He already has it, in his long-term clandestine relationship with Lord and Lady Hernedale. And Lucien is the last man Aubrey should want. He’s a commoner, raised in service, socially unacceptable. Worse, he writes for a disreputable, gossip-hungry newspaper. Aubrey can’t afford to trust him when arrest and disgrace are just a breath away.

Lucien doesn’t trust nobs. Painful experience has taught him that working people simply don’t count to them. Years ago, he turned his back on a life of luxury so his future wouldn’t depend on an aristocrat’s whim. Now, thanks to Aubrey, he’s becoming entangled in the risky affairs of the upper classes, antagonising people who could destroy him with a word.

Aubrey and Lucien have too much to hide—and too much between them to ignore. Rejecting the strict rules and closed doors of Edwardian society might lead them both to ruin… but happiness and integrity alike demand it.

Get this book

Add this book on Goodreads

5 thoughts on “Interview with Jude Lucens”